Production Stamping Built on Diemaking Foundation

“If the walls could speak …” the expression goes. At Miro Manufacturing, Waukesha, Wis., the walls do speak.

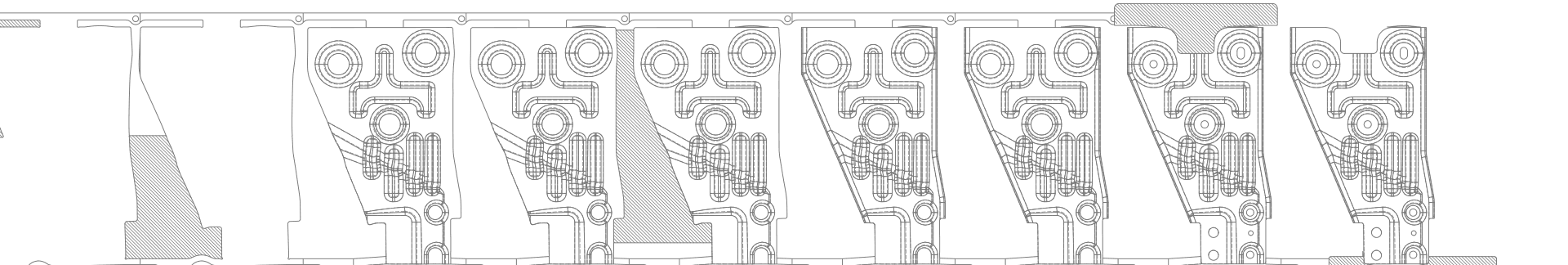

Prog die strips and parts made by single-hit dies line nearly all of the walls of all four of Miro’s buildings. Hieroglyphic-like, they tell a narrative of the type of work the company has done, progressively, and how it has expanded and evolved over the years.

The first strips, beginning in a corner of what was originally a 4,000 square foot building – now a 25,000 square foot building – are small copper and brass stampings, made primarily on small, low-tonnage, one-out tryout presses to test their manufacturability in what was, in 1988, a small tool and die shop. As the stampings make their way along the wall, they grow bigger and more complex. The materials are more varied. Most notably, the stampings transition from impressions for tryout dies to production stampings for assemblies.

“They really tell the story of our company,” said Miro Manufacturing President Jeff Brown.

Although the company has expanded its facilities numerous times and now has four buildings, the walls are no longer large enough to hold all of its stamping samples.

Plan for Presses

When Brown sized up the state of the industry in 2001, he decided he would have to make some substantial changes.

“We read that in the first part of 2001, we lost one-third of all tool and die shops in the U.S. It was a result of 9/11, NAFTA [North American Free Trade Agreement], and opening up foreign markets,” Brown said.

Dave Sucharski, sales manager, added, “Companies were going overseas for cheaper tools. Lasers started coming onto the scene, so the need for trim and blank dies was lessening. Basically, we were a one-trick pony whose industry was diminishing.”

Brown said, “We thought, if we’re going to stay open, we have to look at other opportunities. So we put our heads together and asked, ‘What other markets can we get into so that we can grow?’”

Brown viewed stamping production as an opportunity to even out the peaks and valleys inherent in diemaking. “Diemaking is feast and famine. Every tool and die shop says that because it’s true.”

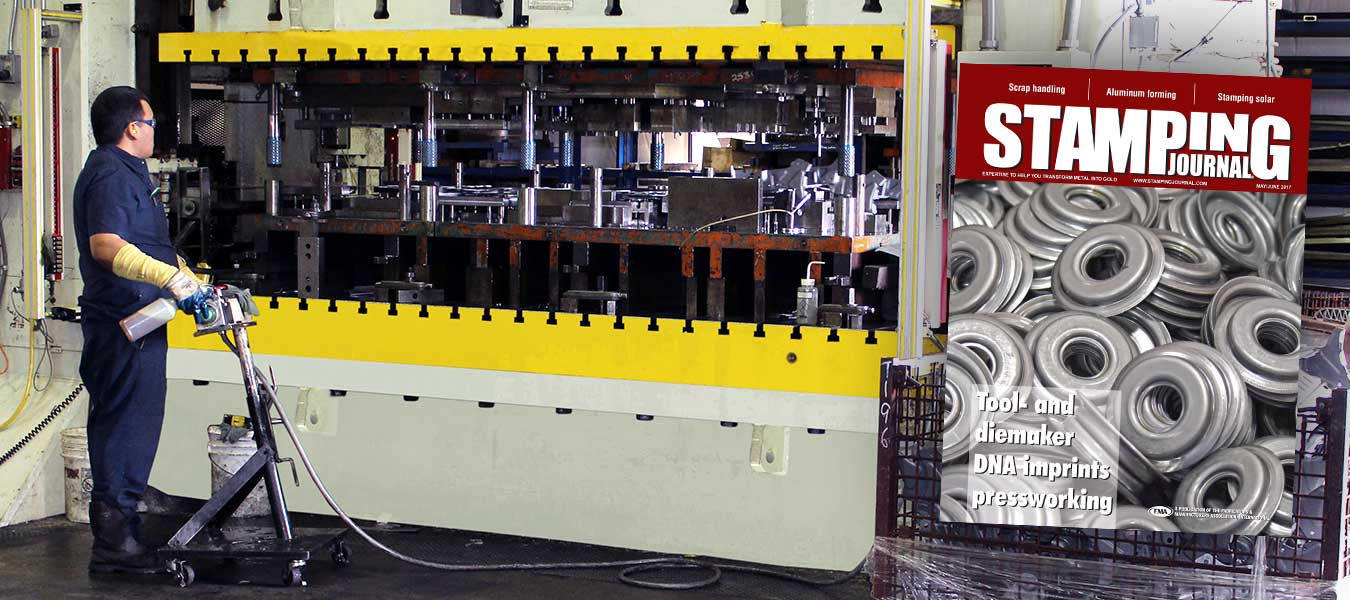

Brown made a pivotal decision: buy big presses and move into stamping production. He bought a 400-ton mechanical press and put it to work forming large parts.

In some cases, Miro simply took over production when customers reached a point at which they needed higher volumes than they were equipped to produce in-house. For example, one customer manufactures aluminum gangways, platforms, and stairs with nonslip surfaces that are pierced and formed to enhance traction.

“A company we’ve had a long relationship with was fabricating them in-house on a turret press and in a press brake. And then their volume started to grow. And they said, ‘You know, there’s got to be a less expensive way to do this. What about stamping dies? Hey, what about Miro?’

“Right now we ship 3,500 of these every month,” Sucharski said.

Another Miro customer was stamping its pulleys in-house. The company ran into a capacity problem. “They asked if we would help and we said, ‘Of course we will.’ And they asked if we had a tool and die room and we said ‘Yes!’

“We’ll tool up and stamp and our customers can save money as their volume grows. Miro’s services aren’t necessarily independent,” Sucharski said.

Scaling up, More Presses

Brown bought a 1,000-ton mechanical press in 2003 to take on even larger work and bought another building to house it and all of its presses. Although Miro has many other presses, Brown considers the 1,000-ton press and a 600-ton Boggs Brown press, purchased in 2015, to be his key presses. The large presses opened doors and helped him distinguish his business from others’.

“At that time we were still 95 percent tool and die. We received a project to tool up an SUV radiator support. The first three strips you see on this wall and a small two-out bracket strip produced the seven parts that make up the red assembly hanging there. The three large dies did not fit the 400-ton, so we had to go somewhere else and rent press time. We didn’t want to do that very long and that’s why we bought a 1,000-ton press,” Sucharski said.

“Everybody had those small presses, and many people could build the small tools. A large press would separate us from some of our competition,” Brown said. But a large press also meant larger support equipment—larger machining centers and larger lifting capabilities. “Everything had to be larger.”

Miro has recently secured a Komatsu 300-ton servo-driven mechanical press that will be installed later this year.

“Servo technology will give us a lead on being more cost-effective for our customer. We will be able to reduce the number of forming stations in a tool and, in turn, the cost of the tool. It means a cost savings for us, too, because there’s less press maintenance. Plus, there is adjustability in being able to program the press,” Brown said.

Into Metal Fabrication

In the middle of 2008, the tool and die industry took another hit. “We lost another third of our industry, so only one-third was left,” Brown said. “That really hurt the whole tool and die industry. We weren’t happy about having less competition, because talent was also diminishing.”

The dire economic situation forced Brown to lay off six people in early 2009—the first and only time the company has had layoffs. “This business is all about people. That was the hardest thing we ever had to do as a family-owned business,” Brown said.

“As the owners who have to look out into the future, we said, ‘We have to do something else to keep the lights on and keep our people.”

The company bought a laser, press brakes, welding equipment, and other metal fabrication equipment and another building to expand into full contract metal fabrication and assembly.

Retains Tool and Die DNA

Just because Miro has expanded into stamping production and assembly doesn’t mean that it has left tool- and diemaking behind. Brown is a tool- and diemaker and says tool and die is in the company’s DNA. Miro has 12 tool- and diemakers on staff and a training program for up-and-coming diemakers.

The training of a tool- and diemaker is all about organization and thought processes, Brown said. “We are trying to train people the same way I was trained. You have to do the whole five-year apprenticeship. You have to know design, understand wire EDM, understand CNCs. It’s really project managing, where you’re managing these tools all the way through the shop.”

Brown added, “You can have all the fancy software to figure out bend allowances and simulation software to figure out where it’s going to crack. It puts you in the ballpark, but it still takes a good toolmaker to figure out ‘What do we have? How can we make this work?’ You still need that person to troubleshoot.”

That tool and diemaker foundation sets the company apart, Sucharski believes. “Many before us have made the transition from tool and die to stamper or contract manufacturer, but many who have made that transition have turned their backs on their tool and die capabilities. Some are capable of basic repairs and maintenance, but we have a complete, full-service, on-site toolroom with capabilities for design and build, engineering changes, and repairs and maintenance—the whole 9 yards,” he said.

Die Rescuer

Sucharski said the company was able to make its foray into new territories because of its die building expertise and even has positioned itself as a “die rescuer.”

“Our tool and diemaking expertise, the ability to troubleshoot and solve problems has put us in a rescuer role,” Sucharski said. “The toolroom sells stamping production work for us.”

One such instance helped rescue a seat belt manufacturer from shutting down an automotive assembly line, Sucharski said.

Rescue No. 1: Height Adjuster Rail. Seat belts are supposed to restrain drivers, not production. A seat belt’s slider mechanism that allows for height adjustment was in short supply at an automotive assembly plant. The Tier 1 supplier was hitting the proverbial wall in trying to manufacture it.

“The part was HSLA grade 80. It was a tooling maintenance nightmare. They couldn’t keep the die running long enough to make enough parts to meet production demand. They were close to shutting the assembly line down. Imagine the daily fee for that!” Sucharski said.

“So they called us and said, ‘Miro, help us. We’re shipping you the die. And we need you to get it running. You have a press. Make us parts.’

“We understand HSLA* very well. You have to build adjustability into the tool to maintain the tolerances. We got the die running, kept it running, produced the parts, and shipped them,” Sucharski said. They wanted to go to the next revision of this part. We did. We built the next die while we were running the old part, and built the new die in record time.” (*High-strength low-alloy steel is a type of carbon steel with enhanced mechanical properties such as hardness, strength and corrosion resistance.)

At its high point, Miro was stamping 1,250,000 pieces a year. The very tough material wreaked havoc on the die for Miro, too. “So the die spent a lot of time in the toolroom while we replaced and repaired parts of it,” he said.

Miro toolmakers took steps that showcased their moxie and toolmaking expertise. They built interchangeability in the tool so that the die could actually be sharpened and adjusted in the press. They added carbide to the cutting stations and a special coating to the forming die steels to withstand the extreme wear the dies underwent while blanking and forming the HSLA material.

“The challenge with HSLA is that there are huge variations in tensile strength. So we analyzed the stations as we were running the die and changed things as we were going along,” Brown said. “On a part like that, you could run 60,000 pieces—that’s just one run—and you have to pull the die out and completely sharpen it. So you have to figure out which is the best material in each station to compensate for the wear.”

Rescue No. 2: Snowblower Framebox. A lawn and garden original equipment manufacturer (OEM) hired Miro to make a snowblower framebox, which holds the engine, axles, belts, and gears. The OEM had been stamping and assembling them in-house. “Someone at the company came to us and said, ‘We are failing miserably; we can’t keep it in production. Please help. You have presses and stamping capability. You have a tool- room. Can you get this die in running condition and produce us some parts?’ When the die eventually made it here, I think there was even some duct tape holding it together,” Sucharski said.

Miro fixed the die and saved the job.

When the OEM readied to design the next version of the framebox, it asked Miro to work with its product designers to make sure the product would be manufacturable. The collaborative effort was so successful that Miro built the prototype tooling, made a few hundred parts, then made changes as needed until the redesigned assembly was perfected. It then built production tooling to stamp and assemble them in full production mode.

Rescue No. 3: Drive Case Cover. A significant aspect of building and reconditioning dies for stamping production is being able to understand the material’s properties and behavior, Brown said. Case in point: Miro rescued a drive case die for a lawn-and-garden industry customer. “The drive case cover is challenging because of the depth of the draw,” Brown said. “The challenging part is the material. You build a tool, which is complicated enough, but to get the right material to draw it consistently …”

“For that reason, our relationships with steel suppliers have to be very good, because you can’t just go to the cheapest guy for the material. Some of the solutions are in working with our steel suppliers to reduce inconsistencies.”

The Rest of the Miro Story

The strips that line the walls speak volumes, but they don’t tell all of the company’s story. Miro is very much a family business. Brown and his wife, Michelle, launched the business in 1988 with a willingness to take a risk and a steely commitment to each other.

“I remember when we started, I asked my wife, ‘Are you willing to lose everything we have? And if you say no, then we won’t go into business.’ My wife said, ‘I wouldn’t like it, but we could get through it,’” Brown said, adding, “And we’ve been blessed.”

Miro is the combination of Miranda and Robin, the names of the Browns’ first two of four children. Michelle has pared down her work hours to one day a week, and she and Jeff are readying to transition the business for the next generation so he can retire in the future. Three of their four children work in the business—two have business degrees and one is finishing his tool and die apprenticeship.

“Being a family business, we’re trying to structure it right now for succession, for the next generation to take over,” Brown said.

It will be interesting to hear what the next generation’s walls will say.

View entire article complete with photos as written by Kate Bachman, Editor of Stamping Journal